How inky footprints are aiding New Zealand conservation.

An edited version of this story was published 19 March 2020, in the autumn edition of 1964: mountain culture/aotearoa.

New Zealand’s native species are in trouble. Thanks largely to introduced predators like stoats, rats, possums, and weasels, we now have around 4,000 threatened species, at least one quarter of which are dangerously close to extinction. The reality of this biodiversity crisis is in no doubt, and since the announcement of the Predator Free 2050 goal in 2016, groups all over the country have been working harder than ever, attempting to control introduced mammalian pests with trapping and poisons. But how do we know where the pests are? How do we monitor the success of a poison drop, or assess the impact on non-target species? In many parts of New Zealand the answer will be the same: tracking tunnels, which allow us to identify and locate pest species by their footprints.

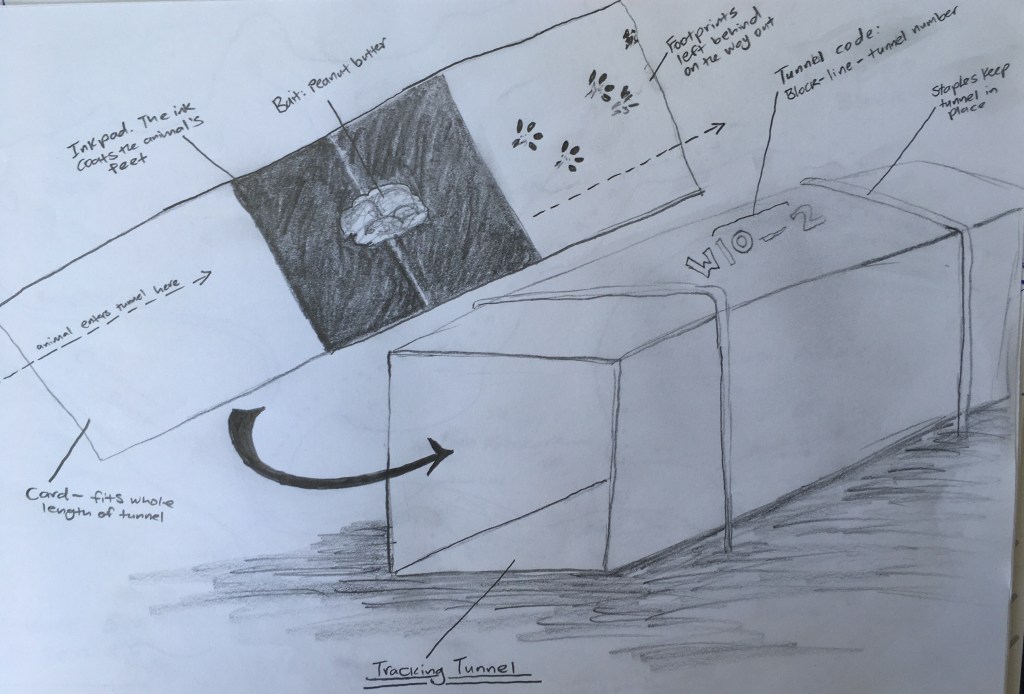

At heart, it’s a simple concept. The tunnel is a rectangular tube of black plastic, open at both ends, which is pegged into the ground. A pre-inked card is inserted into the tunnel, lying flat along its floor, clean and white at each end, with sticky, black ink in the centre. A tasty treat, like peanut butter, Nutella, or a cube of rabbit meat, is placed on the ink to lure predatory mammals in. This means that any animal that wants to sample the bait has no choice but to walk across first ink, then white card, leaving a telling trail of footprints behind them.

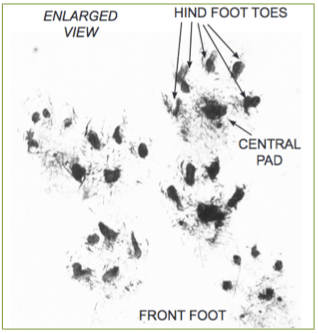

It’s possible to learn a lot about the visitors to a tunnel from their inky prints, and there are all kinds of clues to help identify the species, and even sex of these inquisitive beasts, if you know what to look for. Stoats and weasels have furry feet, the hairs clearly visible as ‘fluffy’ marks between the more solid ink spots of their toes and pads. Possums are easily identified because, in addition to the large size of their feet, they have cushion-like pads, and on the back foot a distinctive opposable ‘thumb’ (despite their large size in proportion to the tunnels, bigger animals like possums and cats have still been known to force their way inside).

Female mammals can be identified by their wide hips, which place their back footprints slightly outside of the front ones creating a zigzag pattern, whereas males have back and front feet that are aligned as if on railroad tracks. Number of toes and size of prints also provide evidence to narrow the investigation down and distinguish between rats, mice, and hedgehogs. While tracking tunnels can’t be used to measure absolute population density (at a certain saturation point the cards simply become too crowded with prints to count), they are good way to track activity changes over time, or compare relative abundance at different sites. Large-scale predator free operations, such as Rotokare fenced sanctuary in South Taranaki, can also use tracking tunnels to screen for re-invading pests.

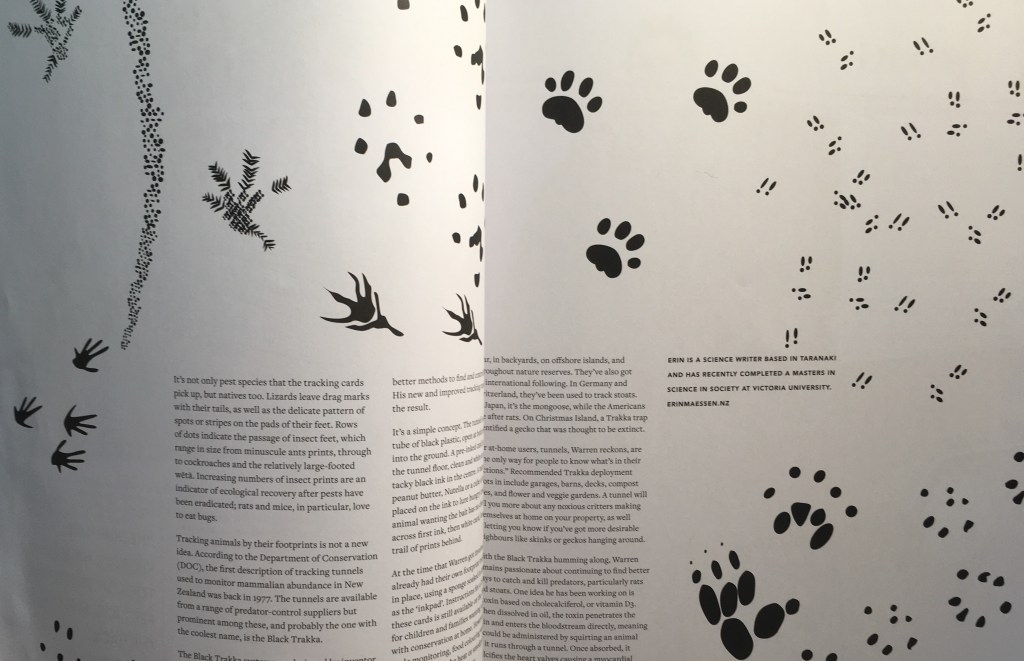

It’s not only pest species that the tracking cards can pick up, but natives too: lizards leave drag marks with their tails, and often the delicate pattern of spots or stripes on the pads of their feet can also be seen. Tiny rows of dots indicate the passage of insect feet, ranging in size from ants, through cockroaches, and up to the large feet of our precious wētā. Increasing numbers of insect prints are one indicator of ecological recovery after pests are removed, for example following poison or trapping operations, as these species also regularly fall prey to rats and mice.

Tracking animals by their footprints is not a new idea. According to the Department of Conservation (DOC), the first description of tracking tunnels used to monitor mammalian abundance in New Zealand was back in 1977. Tunnel varieties are now available commercially from a number of predator-control suppliers, but prominent among these is ‘Black Trakka’, designed by inventor and conservationist Warren Agnew.

Warren’s path to predator control innovation began when he was a teacher at a small rural school, and his class discovered a grey warbler nest. Full of excitement, the children built a hide from which to observe the birds, using an empty coke bottle as a makeshift telescope. However disaster struck in the form of a stoat, one of the most significant and devastating predators of New Zealand birds. Despite Warren’s efforts to chase it away, the villain returned and killed the nest’s occupants.

This incident was enough to spark Warren’s interest, and he contacted the Department of Conservation (DOC), looking for more information. He describes making the call, and being answered “McFaden here, stoat catcher”. Warren was sent reports describing the stoat problem, and set about devising better methods to find and control these predators. His new and improved tracking tunnel system was the eventual result.

At the time that Warren got involved, DOC already had their own footprint tracking system in place, using a sponge soaked in food colouring as the ‘inkpad’. Instructions for a DIY version of these cards is still available on the DOC website for children and families wanting to get involved with conservation at home. However, for large scale monitoring food colouring wasn’t ideal, as it evaporated in the heat, or smudged in the wet, making many records useless.

Finding better materials that would leave clear and lasting marks was key to the success of the Black Trakka system. Warren explains that his main challenges were finding a card that could stand up to New Zealand’s notoriously wet conditions, and a long-lasting ink that wouldn’t dry up. These days Black Trakka has been taken into widespread use, and Warren estimates they now sell around half a million tracking cards each year.

On the smaller scale of at-home users, putting out tunnels is “the only way for people to know what’s in their sections” according to Warren, and might be a good precursor to a backyard trapping operation – traps can even be placed directly into tracking tunnels once a pest species has been detected. In other cases, a tracking tunnel might reveal the more exciting presence of skinks or geckos that might dwell unnoticed in your urban backyard.

Warren remains passionate about conservation, and full of ideas for better ways to catch and kill predators, particularly rats and stoats. One idea he has been working on for some time now is a toxin based on cholecalciferol, or vitamin D3. When dissolved in oil, the toxin is able to penetrate directly through the skin and enter the bloodstream, meaning it could be administered by squirting an animal as it runs through a tunnel. Once absorbed, it calcifies the heart valves causing a myocardial infarction (heart attack), a sudden, relatively painless death that might be more palatable to those who are still hesitant about using poisons to deal with the pest problem.

That might be far off in the future, but for now tracking tunnels and their role in species identification are helping conservationists all over New Zealand in the fight to save our natives from extinction.

For more information about identifying tracks, check out “What made these tracks” a free guide available from Warren’s website Gotcha Traps Ltd.

Leave a comment