– Ten years of change at Rotokare predator free sanctuary

This is an edited version of a piece I wrote in 2018. The original was a science communication assignment for part of my Masters, and is about twice as long as this one.

The country road narrows with every turn and I slow, hugging the corners in anticipation of oncoming vehicles. Hilly farmland spreads out on either side of me, looking scuffed and soggy in the tail end of winter. Sheep run from my car at each corner, and the beef cattle stand clumped together on the flat. And then I come to the top of a blind hill, and everything changes, the grass giving way to a darker green as the place I’ve come to see appears below me.

In the valley ahead of me is the Rotokare Scenic Reserve, 230 hectares of forest amidst a sea of East Taranaki farmland. The name Rotokare, meaning ‘rippling lake’, comes from the three-armed lake at the centre of the reserve. An impressive nearly two metre high fence cuts its way across the hilltops, surrounding the entire reserve and finishing with the double layer of gates now directly in front of me. A square post on my right has a single green button. I have to undo my seatbelt and lean half out of my window to push it. Slowly the first set of gates begins to swing open, and I roll forward into the rectangular ‘cage’, trying to spot all the changes since I last came here.

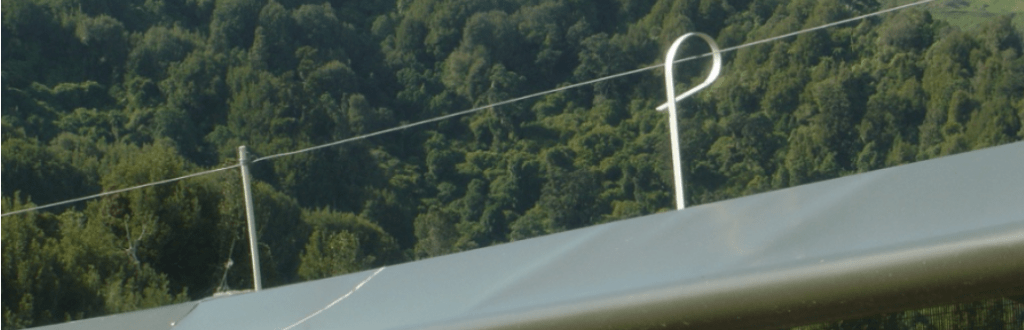

The fence calls an unexpected halt to the steady rolling of the landscape, its green colour doing nothing to blend it subtly with the greens of farmland or bush on either side of it. A wooden skeleton of posts and battens, sturdier and taller than any average farm fence, supports expansive mesh walls that wrap around the reserve, a total length of 8.2 kilometers. If you try to look directly through the fence, your vision becomes fuzzy from the tiny scale of the mesh, small enough to keep even tiny baby mice from squeezing their way inside. Even a single snapped wire could represent a point for pest incursion.

Mounted on top of the fence is the hood, dark green painted steel, sloping towards the farm side to ensure any pest able to jump or climb that high would have nothing to gain a hold on. A single wire runs a hand span above the hood. This is a warning system for possible breaches – if the wire comes into contact with metal, perhaps pushed down by a fallen branch or tree, a signal is sent to the site manager to alert them to the problem. It might not seem like a big deal, but anything leaning on the fence could act as a pathway for climbing creatures such as possums to get inside. The defences even extend underground, with a skirt of mesh designed to keep out burrowing animals. Rotokare is a reverse jail, the inmates free to come and go as they please, the outsiders firmly denied entry unless they have the fine motor control to push the button on the gate.

In my mirror I see the first gate close behind me. I punch the next button, managing to line my car up more smoothly with the post this time, and wait to be admitted. Here in the cage, birdsong has suddenly started up, as if I’ve entered a bubble, separate from the outside world. The second gate is open. I am in.

People have been making the trip over the hills to this secret, forested valley long before there was a road to lead them here. Today, Rotokare is a fifteen-minute drive from Eltham, a small South Taranaki town that’s notable as a place to buy cheese. Once, the lake would have been a brief interruption in the bush that carried on unimpeded from the base of Mt Taranaki in the west. The lake was a short-term visiting spot for the local Iwi, Ngāti Tupaia, to collect resources like food and flax. In the 1960’s people came with boats and picnics, the road was built in 1979, and the first walking track around the lake followed a few years later.

There was never a time when this little spot wasn’t a focal point for the local community, but by 2003, Rotokare was in ecological decline (that familiar story of pest-mammal devastation), and regularly trashed by hoons driving out on a Saturday night. The locals were aware that Rotokare was a unique place, despite the ravages of animal and human pests. At a heated meeting in the Eltham town hall, the decision was made to restore Rotokare both as a functioning ecosystem, and a place the wider community could feel safe to visit and enjoy once again. A dozen or so people put up their hands and the evolution of the Rotokare Scenic Reserve Trust began.

Rotokare is now a predator free sanctuary, one of a few pockets of mainland New Zealand from which pests have been excluded, and a tiny segment of the land returned to its pre-human state – or as close as possible. Karori valley, now known as Zealandia, was the first of these projects, with construction on the fence invented specifically for the job beginning in 1999. Several similar projects followed, including Rotokare, where the fence was closed in 2008. Choosing to erect the 1.9 million dollar fence rather than managing predator numbers through trapping was seen as aiming for the pinnacle of ecological restoration; “the crown jewel, rather than the fake pearl necklace” according to sanctuary manager Simon Collins. Both approaches are important parts of New Zealand conservation, but with different purposes.

A predator proof fence is in no way the best choice financially. A report published by DOC in 2001 modelled the cost over 25 years for exclusion fencing in comparison to conventional control methods – that is trapping and use of bait stations. The study suggested that fencing is a cost-effective option for reserves of 1,000 hectares or greater; however for a smaller sanctuary like Rotokare even the best case scenario of costs will be higher than the worst case scenario using conventional control. Despite this, the report concluded that even in small reserves a fence could provide superior ecological outcomes that justify the greater cost.

A fence is the only method of reliably excluding all pest species from mainland areas, allowing ecological recovery on a scale that would otherwise be impossible. Twelve species of undesirables were targeted at Rotokare, ranging in size from goats down to mice, whereas trapping alone tends to target a few species at most. There are other bonuses too. In New Zealand conservation there is an unfortunate but necessary preoccupation with killing some species in order to save others, which can become disheartening. Since a fence completely excludes pests from an area, control can be maintained in a largely non-lethal way once the initial eradication is over. For volunteers and the wider community this may be more palatable than the ongoing death involved in a trapping and poisoning regime.

Although I’ve travelled the road through Rotokare hundreds of times, it feels very different to be the one driving around these gentle sloping bends, past the yellow diamond-shaped ‘watch for kiwi’ sign, down towards the lake. When I first came here I was 13 years old. Rotokare was my education in New Zealand fauna and the lengths that have been taken to protect it. This was the safe space where I could crash around in the bush alone, and what I did had a real use to conservation. The adults involved seemed to have never-ending time and patience to teach me things. I still remember the pride of helping with vegetation surveys, a part of the team. In 2010 Melissa Jacobson was hired as the reserve’s first environmental educator, building from scratch a programme that went right from early childhood to Year 13’s. Current educator Ash Muralidhar describes the education programme as part of building up the family that will take care of Rotokare long-term: “We had community invested, it was just about maintaining that sustainability, that we bring in younger more vibrant parts of the community to come in and take over those roles”. If the experience these students get is anything like my own then I imagine the reserve is in safe hands.

I loop around the last corner, and rattle over the cattle stop that always used to alert us to the arrival of Gwen and her marvelous lunch at Sunday volunteer working bees. I park facing the lawn, next to the picnic tables, looking out towards the lake. It feels earlier than it is, the clear morning chill seems to cling to this place until midday, the bush around the carpark loud with indeterminate twittering and peeping, occasional trills standing out. A day just getting started, even at ten am.

There seems to be more of everything. More cars parked by the lake; more vegetation, grown up and almost completely hiding the buildings that used to sit starkly out of place at the top of the hill where they had been dropped. More bush too, with new growth of green spilling down to meet the edges of the asphalt, great walls of creepers towering beside the carpark. Fantails bounce around the bush edges at the tops of the trees, mad on the sunshine of almost-spring. The lake glitters, distantly – I want very much to walk down to it. Soon.

I am not just back here to gape at the birds and the bush, although I hope there will be time for that later. I have come to meet with Simon Collins, now sanctuary manager, who started at Rotokare ten years ago, not long after I first came here myself. We meet in the education building, a place that didn’t exist ten years ago, and yet another example of how much has changed. I remember spending a day doing a very poor paint job on the inside of the cupboards here; today it is a different room. Every surface is covered in intriguing collections of objects: boxes of insects, a lizard preserved in a jar, an angry looking stuffed stoat. All bits and pieces that make up the story of Rotokare and its fence.

Today, Simon is wearing a button-up shirt rather than the polar fleece he used to sport in the early days, but apart from this he seems much the same as ever – welcoming, enthusiastic about the reserve, and excited to sit down and tell me all about it. Change is a common theme of our conversation as we sit at the folding table, and Simon fills in the gaps of Rotokare’s history for me.

“Hard to believe we’d be excited ten years later, eh?” he says as the story loops back to the present day.

This is much what I’ve been thinking myself – “It seems like a short time to have changed that much”.

“Seems like a lifetime to me some days!” he jokes, before becoming serious again. “I think you’re right, you know when you look at the timeline and you look at those really pivotal milestone moments… 2006, feasibility study. 2008, well over two million dollars raised, fence complete, eradication done, bang bang bang. It just keeps rolling”.

Simon is incredibly passionate about Rotokare. He came here from Dunedin to become the first site manager when the fence was brand new – his job then included being on call 24 hours a day for alerts of a possible fence breach. He expected to stay one or two years, but ten years later is still here, seemingly for good. When he starts explaining why he loves this project so much his hands wave around madly. What brought him here, and has kept him here so long, is the all-embracing focus that has underlined everything the trust has done from the start. “Everybody is part of this and welcome. And for me that’s the real guts of why it’s so exciting”.

Simon’s first day of work was the grand re-opening following the aerial poison drops that cleared the majority of mammalian pests: day one of a predator-free sanctuary. I wasn’t there for the drop itself, but I remember the fanatical attention to the weather forecast that went on in order to gauge when there would be enough consecutive rain-free days to go ahead, with continual debate and comparison over which forecasting website was the best. Previous manager Kara Prankerd told me at the time that her daily habit of checking and re-checking the weather had become an obsession. Friends who went out on the day told me later how they were stationed outside the fence, watching intently for any pellets that spilled over into the surrounding farmland as the helicopter delivered its load.

The trust planned for three rounds of poison using pelleted Brodifacoum, an anticoagulant toxin. In the end they only needed two, a relief as unlike the better-known poison 1080, Brodifacoum bio-accumulates, meaning that it can have lingering effects, and the least used the better. However the use of poison was never in question at Rotokare – as the island models before them had shown, initial poison pulses are key to successful eradications. Fernbird were monitored as an indicator species to gauge the effect of the poison on non-target species. Counts pre- and post- poison dispersal provided a baseline, but the result was a population increase. As for other species, it is unknown whether robins were killed during the eradication, but they certainly returned – Simon remembers sighting the first post-eradication robin late in 2009.

In a situation like this, deaths have to be kept in perspective. Death of a few individual robins is deemed acceptable when it is the cost of saving the species. Simon explains that at times a place like Rotokare has a strong analogy to farming, with a certain rate of attrition. This is made particularly clear because this morning one of the reserve’s next-generation kiwi was found dead by misadventure, having fallen in a pond.

“It’s normal” Simon explains firmly. Despite the care and attention invested in the species’ recovery, mishaps do sometimes occur. “It’s nothing to be sad about… Things do not always live”. As long as the rate of output is greater than decline, then the population remains a normal, functional one, which is the real goal. “Isn’t it great that we have kiwi here in the first place”.

I am impatient to get out in the reserve and see the changes Simon describes for myself, so I say goodbye, and head down towards that still-glittering lake, only pausing briefly at my car to collect my backpack. Stepping into the bush, I feel a sense of spreading calm. The breeze is warm – it could be summer if I wasn’t wearing a thick merino jersey – and there is a familiar smell to it. Something thick and wet and green, the smell of leaf litter and moss. I sit myself on a slightly damp wooden bench with its back to the main track, facing a gap in the bush that gives me a narrow view of the lake. The opposite shore is fringed in reeds and grasses, and beyond that rises the beautiful, impenetrable wall of the bush. Hungry now, I chew my way through dry sandwiches without caring what they taste like. I am impatient to be back on my feet and exploring on around the lake, but at the same time reluctant to leave the contented feeling I have sitting quietly in this place. I want to see everything, but I want to pause over it too. I stand up before the damp can soak too far into my jeans, and carry on.

The bush is noisier than I remember it. Scratching sounds in the leaf litter on either side of the track announce the presence of saddleback, sometimes making themselves more obvious by their piercing siren warning call when I approach. Perhaps in the early days these scrabbling noises would have been cause for concern, bringing up fears of rat or mouse invasions. Now saddlebacks potter in the leaf litter, unaware of how momentous their very presence in this place is. I regularly change my mind about which native bird is my favourite, but today it’s the saddleback. A little further on, a tomtit darts from branch to branch, refusing to keep still long enough for me to take a photo of it. It feels good to be here to see these birds, knowing as I do just a small part of the hard work that went in to reaching this point. Speaking of that hard work though… A glance to the side every fifty metres or so as I walk, and I spot a blue plastic disk nailed to a tree, and beyond that a dangling trail of pink tape leading into the bush, the biggest nostalgia hit of all.

Once the fence was up and the poison drops had cleared out most of the unwanted mammals, an epic 18-month clean up period began, with monitoring and trapping across the entirety of the reserve. This is how I remember Rotokare: dripping green bush, the smell of peanut butter, black leaf litter, crawling up banks almost on hands and knees, clutching at loops of supplejack that both hinder and help as you attempt to keep moving forwards and upwards without snagging an ankle. Following ribbons of pink tape on a bizarre treasure hunt through bush that still seemed completely impenetrable even when you walked the same route twice a month. Getting hopelessly lost any time a fallen branch or downed tree disturbed the trail. Wading through swampy sections of native begonia, Parataniwha, imagining that if New Zealand had snakes, this is where they would hide. And all this in pursuit of unobtrusive black plastic tunnels, stapled into the ground every 50 metres right across Rotokare.

The tracking tunnel is a square tube of thin plastic, about half a metre long, into which a white card with an ink pad at its centre is inserted. Getting the card into the tunnel without touching the ink is a bit of a trick – my raincoat and most of my ‘bush clothes’ had permanent black fingerprints all over them, and smears where I’d attempted to clean my fingers. The idea is simple. You entice an animal into the tunnel with bait placed in the middle of the ink – peanut butter is best, though in the early days we added a chunk of frozen rabbit meat as an extra incentive. Animal goes in, walks on the ink, and leaves its footprints on the white card as it leaves.

To an educated eye it is possible not only to tell what species visited a tunnel, but often also the sex of that individual, an important consideration when you are always on the lookout for pregnant females that could equal disaster with the speed of increased numbers. When the fence was first built, the cards came back black with the prints of rats and mice. After the poison drop they started to come in as clean and white as they went out. Real success was when the tiny spots of insect feet began appearing, indicating an ecosystem slowly restoring itself as these unnoticed links in the chain recovered in the absence of predation by rats and mice that had devastated their populations.

The tracking tunnel lines were planned according to GPS. Dividing the reserve into fifty metre sections sounds simple in theory, but is a lot more complicated once you’re out there dealing with the topography. The worst part was when you made it up a vertical cliff only to realise you’d missed a tunnel, or left something behind. I lost countless pencils throughout Rotokare, and always travelled with a couple of spares to save myself painful and disheartening backtracking. Sometimes you’d get your lost possessions back on the next visit. Other times it seemed like the bush consumed them. One memorable month, prizes were randomly assigned to some of the tunnels in an attempt to keep us volunteers going, and add some variety to working our way along lines that were starting to become extremely familiar. I went home that day with a stash of marshmallow Easter eggs for my efforts. Now that the reserve and its pest-free status are well established, tracking tunnel lines don’t need to be run as often. This has become a six-monthly checkup, a snapshot of the reserve to ensure all is still well.

The volunteer effort involved in creating the Rotokare I see today was immense, and at times it was hard, even demoralising. Despite the overall success of the eradication, there were times when rats, mice, and once a pair of stoats were detected. I remember tracking tunnel lines mostly as a fun way to spend a day, but sometimes it was wet, or cold, or frustrating. Every month for eighteen months, volunteers laid out tracking cards across the entire reserve, then collected them back in a week later. But the full extent of volunteer hours went far beyond that. The fence had to be regularly inspected for any damage. The three buildings that arrived as empty shells had to be brought up to shape. Boardwalk was built on the muddiest sections of the walking track. Steps were cut into the ridge to help make the fence line more accessible to volunteers, and later a section of the ridge was developed into a second walking track.

Hundreds of trees were planted to fill in the grassy areas, mostly in daylong efforts. The first day of planting was so cold that we had difficulty chipping though the frosty grass to dig holes, and each tree came with its own block of ice frozen around the roots. Another project that consumed hundreds of volunteer hours was knocking on doors throughout the district, petitioning residents to make submissions to the district plan on Rotokare’s behalf. The result was 700 submissions in favour, and an annual grant that the trust still receives today.

Rotokare has always been a community driven project, created by collaboration of recreational users and conservation enthusiasts, which is why there has never been any question that recreational use should continue. However having a sanctuary that vehicles can drive into does add complications. Signs along the road into Rotokare urge visitors to check vehicles for rodent stowaways, particularly in boats that may have been left dormant for several months. I remember the feeling of trepidation each year when the boating season started, checking tracking tunnels nervously in case rats or mice had been delivered in an uninspected boat.

Mice have been the bane of every mainland sanctuary’s existence, with most opting to co-exist with this smallest of mammalian pests, and simply manage their numbers to a bearable level. Although Rotokare has a had a few mouse invasions – the worst in 2016 – they have always managed to regain control and mouse-free status. Simon is resolutely modest about this achievement and names luck as the main factor, another story helps explain why mice were eradicated so successfully in the first stage.

Before building the fence, a feasibility study was carried out to determine whether it would be right for Rotokare. It concluded the most effective option would be for the fence to run along the ridge tops that circle the lake and its remnant bush. This way trees were less likely to fall on the fence, and rats and other undesirables wouldn’t be able to get in by jumping tree to tree. Horizontal jump distances were one of the things tested when predator proof fences were first being developed – a clear gap of four metres is needed to keep out rats. That view as you approach the Rotokare front gate is striking for a reason, with the fence marking a firm boundary between farmland and bush, all the trees safely on the inside. The original Rotokare reserve, pre-fence, wasn’t this clear-cut – to make it happen, neighbouring farmers donated an extra 12 hectares of land.

The downside was that not all of the extra land was bush. Instead, sections of the soon-to-be fenced Rotokare were dressed in long thick grass, the perfect hiding place for hares, rabbits, rats and mice to escape the poison drop. The grass also represented an abundant source of food, more plentiful and palatable than the poison baits, clearly an obstacle to successful eradication. In a display of resourceful community spirit, one of the local farmers offered to lend his sheep to the reserve, to graze out the area before the poison went in. DOC, concerned about any potential harm to the native environment, told the trust they were not allowed to use the sheep. According to the way Simon likes to tell the story, “on Friday they said no, so on Saturday we put the sheep in”. The sheep stayed for a month, grazing the grassland to the ground, and once nothing was left they were moved out and the bait went in. Although there were many factors at play, the Trust attribute a significant amount of the eradication’s success to the surreptitious sheep operation.

A circuit of the lake takes about an hour and a half, although when you stop to look at every saddleback you hear this timeframe is considerably extended. I am starting to get tired by the time I get back to my car, and wonder how 15-year-old me could crash up and down those steep banks for so long. I sit myself down on the edge of the open car boot so I can unlace my muddy boots, another familiar tradition. Not so long ago, we would trek back out of the bush after a hard morning’s work, cold, wet, and tired, and ready for a hot lunch, and dream about the day when the empty bush at Rotokare could start accepting back its rare and treasured species. Out on the lawn, a couple of pukeko roam around between the picnic tables, probably looking for interesting crumbs left behind. It is not difficult to imagine a few takahe joining them someday.

I first visited Rotokare just over ten years ago. In such a short time, it’s incredible how much has changed. However as I drive back up the winding road towards the gate, it is the familiar that stands out to me the most. The old bush, still standing. The mighty fence standing around it. Slowly, I reverse the process of button and gate, and cage, and button and gate. It’s mid afternoon now, and the farmland looks more cheerful in the sun. The forest falls behind all too quickly, and then suddenly I dip back over that hill, and Rotokare is gone.

Once again, all I can see around me are the grassy hills and the mountain in the distance – it would be so easy to forget there was anything special waiting behind the hills. A bird darts across the road in front of me, and into the bushes at the side. It’s just an ordinary blackbird, but all of a sudden I wonder what it would be like to be driving this road and see a saddleback cross in front of me. Or a robin. Or maybe one day a kaka. I wonder how long it will be before Rotokare spills out its secrets right across the ring plain, and the everyday farmland fills with species that once looked set to vanish completely.

Erin Marieke Maessen

October 2018

This project could not have been completed without the help of wonderful people at Rotokare – thanks to Simon Collins and Ash Muralidhar for taking the time to be interviewed.

For more information about the Rotokare reserve, visit their website: http://www.rotokare.org.nz/

LikeLike